I finished my placement in Durham County Record Office (DCRO) just before Christmas, but it took me a while to sit down and start writing this. My three months in Durham meant a lot to me, so I needed some time to gather my thoughts about everything I learnt and lived there.

My arrival in Durham was a bit unexpected for me. I was finishing my masters last July when I found out I got a grant to do a placement abroad. As a history student who always liked researching, I thought the perfect experience for me would be in an archive, where I could learn about the profession and improve my knowledge of that environment. After looking at different places online, I sent some emails and received a very quick response from DCRO. I did not hesitate for a minute and said yes. For a medievalist like me, the view of Durham cathedral and the story of the city were more than enough to make that decision. And it turned out to be a very good decision.

I started the placement at the beginning of October and I knew part of my work would be for the Durham at War Project, but I could not imagine that it would be most of it. At the end, I spent more than a month and a half working on it. For the rest of my time there I transcribed and translated different materials, some of them for the project too, and I was trained in different archival tasks such as cataloguing, activities that I also enjoyed.

My work for the project consisted of researching stories using a range of online resources, writing those stories and uploading them to the Durham at War website. I remember the first days when I discovered tools such as Ancestry and Find My Past. ‘Why do we not have things like these in Spain?’ I kept thinking.

One of the things I immediately liked about the project was the perspective it was from: bringing alive the stories of those involved in the war, but also the way of living during that time, the events people had to go through… and all focusing on County Durham, so people related to this area could have all this information easily available. The project meant that everybody could learn about this past, look for their relatives and also participate and contribute with their own memories and stories.

I remember some of the first people I wrote about, they were men born in County Durham who served in the Australian or the Canadian army; I particularly liked these stories because behind their military service there was also the story of their emigration.

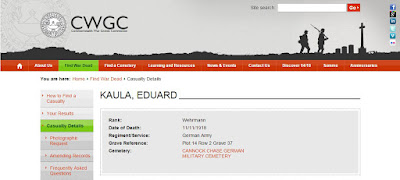

Soon after that, I started to work with

John Sheen’s collection: photos and stories I had to research, write, and upload to the website. I worked with this collection for a long time, finding all kinds of stories of many different men and families, stories that touched me and made me think, and that actually ended up being part of me. As I said one day about them: “I dream about these men”. And, in fact, I still remember some of them, even their names:

Charles ‘Wardy’ Ward, Ralph Cherry, the three Clark brothers who were killed in action, the pictures of the DLI in Cologne, the sport days of the 20th Battalion… And here I would like to thank John, first of all for his kind words about my work, but especially for collecting these stories and making sure they are kept alive.

But, as I soon discovered, John was not the only person who was interested in the project. Volunteers who wanted to participate came to the office frequently, they wanted to help and were happy to research, transcribe, revise stories… Along with them, I met other people from different associations who were working on projects about the First World War as well, but also many people just interested in knowing more about this time, even some of them looking for their relatives. That so many people wanted to learn more about their history made me very happy, but also surprised me a bit.

In my previous time living in England I had already realised the different relationship that exists here with history compared to Spain. I remember being surprised by all the memorials, always full of poppies, which are in every single city and small town. Of course, I know Spain was not involved in any world war, and remembering a civil war is never easy, but even so I feel we are a step behind appreciating and respecting our history, which leads to a low interest and engagement with our past.

In this sense, I kept remembering the search room of the local archives I used to visit back in my home town, where normally it was just me in the room, often me and my dad, and sometimes one or two more people. In the search room of Durham Record Office there were always so many people looking for things, reading, consulting records, researching on Ancestry…

|

| The searchroom at Durham County Record Office |

Meeting all these people interested in history made me think one more time about how important it is that everybody knows about their past and especially that they engage with it. And all of these people, with their particular interests, researching for the project or for their own personal purpose, were contributing to making history by gathering together part of that past.

Because of this, I would like to congratulate everybody who is part of Durham at War, including all the volunteers, for their work. And, of course, everybody in Durham Record Office for the time I spent with them: thanks for making me feel comfortable from the first moment, for your help, for your support, and for your fantastic work every day.

I know I do not work on the project anymore, and this is probably my last contribution to it, but I hope after what I wrote you understand why this experience meant so much to me. Now, I frequently find myself thinking about all of these ideas, but also reading everything I see about First World War, telling everybody who wants to listen (and even if they don’t) some stories I remember, and I even stop by the memorials and plaques to read the names!

And this is it, how a history student specialised in the Middle Ages ended up reading British censuses from the 19th and 20th centuries. A bit of a change, you might think. In fact, it was. It was a good and interesting change that gave me the opportunity to bring history to people, improve my research and palaeography skills, my historical knowledge about the First World War and especially enriched the most human side of the historian I am trying to be.