|

| Frasne station, France, Vincent de Morteau, Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 |

On 26 January 1917, Connie writes to her mother and father and tells them 'the supposed air raid was a fire alarm only, so no excitement.' The Officer who had taken their tickets returned them with an account of what he had paid for the upgrade to first class for Paris to Lausanne, the sleeper car and registering their luggage through to Chateau d'Oex. He changed Connie's last £5 for her. The hotel bill came to 21 francs for the two of them, bed, early breakfast and dinner of four courses, 'wasn't it reasonable?'

At 9.30pm they were taken to the station, boarded the train, and were soon in their bunks. Connie was worried in case she might sleep in, as she wasn't sure that the attendant understood when they wanted to be called. 'One incident was amusing, I rose and dressed about 5.30am … I went along the corridor and as our door did not latch very well I looked for something to prop against it, I spied a bolster pillow amongst a heap of what I thought bundles of carryalls, pulled it away, when suddenly the supposed bundles leapt to life as the attendant, I got a great shock, and quite forgot for the minute that my explanations in English were no use. However, I just had to leave the door open; he didn't seem to understand I wanted him to put his head against it to keep it shut.'

I have a suspicion he did know what she wanted him to do but possibly being a little disgruntled having been rudely awakened, he decided he didn't want his head used as a doorstop.

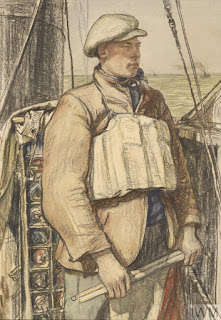

Arriving at Frasne [France], a little wayside station, about 7am, Connie and Miss Selby alighted amongst snow. It was bitterly cold and they were kept waiting in a shed without seats for some time despite being, 'amongst the first'. Here they went past the customs and were asked if they had any English gold or silver or any letters to post. A French woman was taken away to be searched but they got through all right. The waiting room was very similar to Birtley except smaller, and a peasant woman had hot coffee and rolls on the table which they enjoyed. On to Vallorbe [Switzerland], where all their luggage was deposited on a counter and everyone's things searched but theirs. Once Connie managed to get them to understand they were travelling with the Red Cross they chalked them and off they went, 'one more good turn that I have to thank Mr Wilkins for.' They take the train from Lausanne to Montreux and they had lunch on board. They were naturally disappointed when there was no one to meet them, but concluded that they must have met the Wednesday train (as wired) and didn't know what else to do when they hadn't turned up. Undaunted, Miss Selby and Connie went on alone.

|

| Rising above Montreux on the line to Les Avants and Rossiniere, Switzerland, photo by Victoria |

Connie describes her long awaited meeting with Angus in her diary:

'The little Electric train zig-zagged up the mountain side, we rushed like school children one side of the train to the other, as the view changed sides or appeared to... As we climbed higher, we saw the people tobogganing, and skating, and about halfway up the mountain, a crowd, watching the finish of some bobsleigh races, and there, there was Angus, watching for me, he had just finished his race, and had come on to the platform to see if I was there, as he had been doing for three days, he didn't hold out much hope of seeing me on this train, my second wire had not arrived, and when enquiring about the Red Cross Wives Party he was told none were expected, (but that was because our Red Cross lot were bound for Murren this time). I got out quickly, Miss Selby promising to put my luggage out at Rossinieres.

I cannot give my reactions to the Life that greeted me at Les Avants, all were in holiday mood, winter sporting except for the khaki and the men who were wounded, armless or legless, or crippled, it was a pre-war winter sports holiday scene. I felt shy at being introduced, not feeling my best after travelling for 3 days and nights. Angus was in the next race, and when I saw his team of four coming down the run, iced, banked high at an angle at the corners, with a yell that echoed round the hills as each corner was safely manoeuvred, and the final flash past the winning post out of a narrow avenue of pines, my heart stood still, but it was great- and the English Team won! And...’

SPOILER ALERT

‘...we have the little silver cup Angus got to this day.'

Sorry for the spoiler alert: I am trying to reveal the story as it was revealed to me. Connie's diary provides an interesting contrast between what she chose to write in her letters to her parents and how she described the same events in her diary.

They boarded the next train coming up from Montreux along with the other British interned soldiers and their friends. They both felt very self-conscious as everyone went to the other end of the long compartment to leave them to themselves. At Rossinieres they alighted and climbed up a narrow path through the deep snow to where Angus, his mother and sister were staying. Connie was reminded of 'the slanty climb from the main road up Peggy's Bank, with the Hotel at the top … I felt all eyes were on me, the fiancee from England who had taken so long to get here.'

Connie naturally misses out most of the details of her meeting with Angus in her letter to her parents, but she does tell them that Mrs Leybourne and Angus’ sister, Muriel, were so pleased to see her. 'They had been to Montreux three days to meet me, it is a long way from here, and had arranged for a lady to meet me the following days in the week, but I had apparently missed her. Will have to stop, will continue in my next, so happy … Heaps of love. Your bairn Connie Kirkup.’